Book

Review: The Warmth of Other Suns

Using history to support exploration

of past and current race relation issues.

Karen White, Ph.D.

Summer may finally be

emerging in the Chicago area. And summer in Chicago

means incredibly good, free music festivals….such as the Gospel

Music Festival in May, the Blues Festival in June, and the Jazz

Festival in early September. Why do Chicago music festivals come

to mind in a review of Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other

Suns? Because without the mass migration of American

Blacks from the US South to the North and West, Chicago might only

be “appreciated” for its extreme winter weather and blow hard

politics. Chicago culture was forever enriched by the

infusion of music originally developed in the American South by

enslaved Africans and their “freed” descendants. Wilkerson’s

book is about far more than the African American influence on

music in Chicago. It offers a view of American history that

is rarely recognized.

Summer may finally be

emerging in the Chicago area. And summer in Chicago

means incredibly good, free music festivals….such as the Gospel

Music Festival in May, the Blues Festival in June, and the Jazz

Festival in early September. Why do Chicago music festivals come

to mind in a review of Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other

Suns? Because without the mass migration of American

Blacks from the US South to the North and West, Chicago might only

be “appreciated” for its extreme winter weather and blow hard

politics. Chicago culture was forever enriched by the

infusion of music originally developed in the American South by

enslaved Africans and their “freed” descendants. Wilkerson’s

book is about far more than the African American influence on

music in Chicago. It offers a view of American history that

is rarely recognized.

Wilkerson brings to life the Great

Migration that took place between 1915 and 1970, a journey that

followed along three train routes leaving the South to cities

along the eastern seaboard, the industrialized upper Midwest, and

Los Angeles and Oakland areas of California. Many European

Americans have a strong sense of the immigrant stories of their

own families, but few appreciate the challenges placed on African

Americans’ efforts to break free of the post-emancipation

oppression of poverty, the indentured servitude of sharecropping,

and the extreme inequities of the educational system in the South.

Although African Americans may have escaped the overt

discrimination of Jim Crow laws in the South, their efforts to

make a better life in the North and West were often thwarted by

subtle and outright prejudice in crowded cities where there was

intense competition for resources among White and Black

“immigrants”.

The beauty of Wilkerson’s craft is evident in her presentation of

three individual stories of migration; each person from a

different decade of the Great Migration, each with a different

destination (Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles). The

unfairness of sharecropping economics, the threat of the Klan, and

the disrespect of one’s hard earned advanced education are all

made palpable in the stories of Ida Mae Brandon Gladney, George

Starling, and Robert Foster. In describing the lives

of these individuals in almost novel-like form, Wilkerson

engenders an appreciation of the motivation to leave one’s home in

the South and the tremendous courage required to take such risks.

The stories are imbedded in a deeply contextualized presentation

of the times and segments of black society in which each person

lived. Wilkerson conducted more than a thousand

interviews and consulted hundreds of printed sources.

Wilkerson’s masterful storytelling brings one to a new

appreciation of American history and why we might be looking at

today’s wrenching stories of frustration and violence in urban

settings.

The beauty of Wilkerson’s craft is evident in her presentation of

three individual stories of migration; each person from a

different decade of the Great Migration, each with a different

destination (Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles). The

unfairness of sharecropping economics, the threat of the Klan, and

the disrespect of one’s hard earned advanced education are all

made palpable in the stories of Ida Mae Brandon Gladney, George

Starling, and Robert Foster. In describing the lives

of these individuals in almost novel-like form, Wilkerson

engenders an appreciation of the motivation to leave one’s home in

the South and the tremendous courage required to take such risks.

The stories are imbedded in a deeply contextualized presentation

of the times and segments of black society in which each person

lived. Wilkerson conducted more than a thousand

interviews and consulted hundreds of printed sources.

Wilkerson’s masterful storytelling brings one to a new

appreciation of American history and why we might be looking at

today’s wrenching stories of frustration and violence in urban

settings.

Wilkerson covers seven decades of a continuous stream of

migration, and it should not escape us that although we are many

years past the “Civil Rights Era”, our society is struggling to

face an ugly scene of African Americans being unjustly arrested,

abused, and murdered at the hands of “authorities”.

These injustices placed in the political context of an African

American president, and now the second African American attorney

general, cause us all to wonder how to understand the enormous

advancements and shockingly slow progress for a group of Americans

who, as a group, have been in this land longer than most European

Americans. Our current graduate students have certainly

grown up in more integrated schools and peer groups, but may lack

an appreciation of how and why race relations in this country

remain such a painful, threatening topic to broach in a group

context. Perhaps Isabel Wilkerson’s book is an opportunity

for all of us to deepen our sense of history about American

culture. It may be one way to draw graduate students (and faculty

colleagues) into an exploration of diversity issues. Wilkerson’s

book invites an appreciation of our recent history and the

complexities of race relations. Her beautiful prose and deep

understanding of history should hold our minds open and make us

curious about the American experience in all of its shades and

stages.

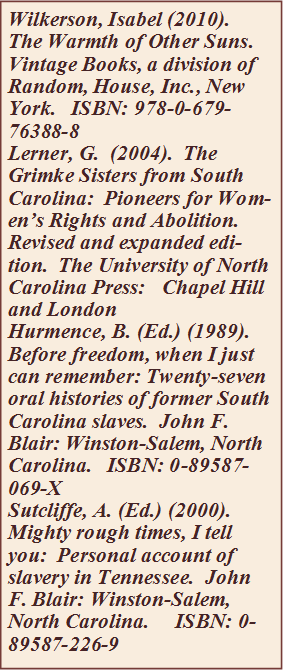

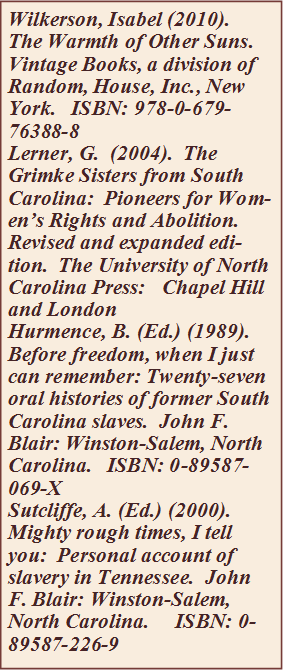

Understanding today’s issues may require

us to step beyond our own time-locked point of view.

Consider exploring even brief segments of Wilkerson’s book for

group discussions. In addition, below are listed some

other books. One is about female abolitionists from South

Carolina. Two other books are from the perspectives of individuals

who were born into slavery. The Library of Congress sponsored the

Federal Writers’ Project which created work for jobless writers

and social workers to interview African Americans who had lived

under slavery. The interviewees were at least ten years old at the

time they were freed and were interviewed during the Great

Depression as they approached their 80s and 90s. Reading

historical work from the perspective of individuals who lived it

sometimes pulls us in to a space more conducive to reflection on

the human experience.

Summer may finally be

emerging in the Chicago area. And summer in Chicago

means incredibly good, free music festivals….such as the Gospel

Music Festival in May, the Blues Festival in June, and the Jazz

Festival in early September. Why do Chicago music festivals come

to mind in a review of Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other

Suns? Because without the mass migration of American

Blacks from the US South to the North and West, Chicago might only

be “appreciated” for its extreme winter weather and blow hard

politics. Chicago culture was forever enriched by the

infusion of music originally developed in the American South by

enslaved Africans and their “freed” descendants. Wilkerson’s

book is about far more than the African American influence on

music in Chicago. It offers a view of American history that

is rarely recognized.

Summer may finally be

emerging in the Chicago area. And summer in Chicago

means incredibly good, free music festivals….such as the Gospel

Music Festival in May, the Blues Festival in June, and the Jazz

Festival in early September. Why do Chicago music festivals come

to mind in a review of Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other

Suns? Because without the mass migration of American

Blacks from the US South to the North and West, Chicago might only

be “appreciated” for its extreme winter weather and blow hard

politics. Chicago culture was forever enriched by the

infusion of music originally developed in the American South by

enslaved Africans and their “freed” descendants. Wilkerson’s

book is about far more than the African American influence on

music in Chicago. It offers a view of American history that

is rarely recognized.  The beauty of Wilkerson’s craft is evident in her presentation of

three individual stories of migration; each person from a

different decade of the Great Migration, each with a different

destination (Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles). The

unfairness of sharecropping economics, the threat of the Klan, and

the disrespect of one’s hard earned advanced education are all

made palpable in the stories of Ida Mae Brandon Gladney, George

Starling, and Robert Foster. In describing the lives

of these individuals in almost novel-like form, Wilkerson

engenders an appreciation of the motivation to leave one’s home in

the South and the tremendous courage required to take such risks.

The stories are imbedded in a deeply contextualized presentation

of the times and segments of black society in which each person

lived. Wilkerson conducted more than a thousand

interviews and consulted hundreds of printed sources.

Wilkerson’s masterful storytelling brings one to a new

appreciation of American history and why we might be looking at

today’s wrenching stories of frustration and violence in urban

settings.

The beauty of Wilkerson’s craft is evident in her presentation of

three individual stories of migration; each person from a

different decade of the Great Migration, each with a different

destination (Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles). The

unfairness of sharecropping economics, the threat of the Klan, and

the disrespect of one’s hard earned advanced education are all

made palpable in the stories of Ida Mae Brandon Gladney, George

Starling, and Robert Foster. In describing the lives

of these individuals in almost novel-like form, Wilkerson

engenders an appreciation of the motivation to leave one’s home in

the South and the tremendous courage required to take such risks.

The stories are imbedded in a deeply contextualized presentation

of the times and segments of black society in which each person

lived. Wilkerson conducted more than a thousand

interviews and consulted hundreds of printed sources.

Wilkerson’s masterful storytelling brings one to a new

appreciation of American history and why we might be looking at

today’s wrenching stories of frustration and violence in urban

settings.